Living with trauma can feel like walking around in weighted clothing–vacillating from strands of gossamer one moment to chain mail the very next. It’s something to get used to for sure, and having a set of healthy coping skills is paramount. The coping skills themselves have to be developed by each survivor over time, by trial and error, especially since one person’s coping skill can be another person’s trigger.

I’ve written elsewhere about my trauma toolkit (The Treatment Method That Was a Game-Changer for My PTSD). One tool I didn’t mention is how horror films help me feel safe during a PTSD episode. Not just any horror films, mind you. I’m talking about transgressive, sick, twisted horror films. The more upsetting up the better. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (the original), Antichrist, The Evil Dead (the original), Night of the Living Dead, The Midnight Meat Train, Hostel, I Spit on Your Grave, The Human Centipede, Antichrist, I Saw the Devil, Mother!, Dogtooth, A Clockwork Orange, Funny Games, Oldboy, High Tension, The Last House on the Left, Irreversible, Get Out, Midsommar, 28 Days Later, 28 Weeks Later, Dawn of the Dead (both versions, but mostly the 1978 version), to name a few. (If you have others, please put them in the comments as I’m always looking for more.)

It might sound strange to say that watching The Texas Chainsaw Massacre soothes me when trauma has taken over my body. But it does. In a section from The Body Keeps the Score called, “Addicted to Trauma: The Pain of Pleasure and the Pleasure of Pain,” Bessel van der Kolk writes that:

Many traumatized people seem to seek out experiences that would repel most of us, and patients often complain about a vague sense of emptiness and boredom when they are not angry, under duress, or involved in some dangerous activity (31).

Van der Kolk’s way of framing the question is not quite the way I’d put it. The “emptiness and boredom” has to be put into its proper context. If a person lives most of life in a hyper-aroused state of fight or flight (as many trauma survivors do) then the opposite of that–“not angry, under duress or involved in some dangerous activity”–can be a real shock to the system. Recovery from trauma might be viewed as the recovery from hyperarousal, which is nothing short of rewiring the brain.

Viewed through this lens it should no surprise that traumatized people seek out less harmful experiences that mimic or echo the feeling of hyperarousal caused by the original trauma during the long arc of recovery. For me, horror films are a safe way to reenter the traumatic space temporarily as I adjust to non traumatic spaces.

But that’s not all. I find horror films comforting because they depict a world in which really bad things happen, a world where what happened to me is normalized. When I watch these movies, I feel like the filmmakers understand the one thing about me that most people can’t: how it feels to live with trauma. Horror films are transgressive, and their stories exists in hyperreal spaces outside of “normal” modes of behaviors and social codes.

Horror films are also ficton, and as fiction they can provide the visceral experience of being traumatized with an ending. When Sally Hardesty is tied to a chair in the The Texas Massacre‘s third act and forced to be a part of the worst dinner party ever, it reminds me of being held against my will. That probably sounds dark so let me try to get to the light. Sally gets away. She endures the horror in the house, and she gets away. Even if the character doesn’t get away, which happens more often than not, the film itself ends. Part of watching a horror film is being able to leave at any time.

Carol Clover is an American professor of Medieval Studies and American Film at the University of California, Berkeley. In her book, Men, Women and Chainsaws she provides a broad analysis on the importance of horror films–why we should study them, what they mean, and what they say about us. In the introduction to that book she writes:

Our primary and acknowledged identification may be with the victim, the adumbration of our infantile fears and desires, our memory sense of ourselves as tiny and vulnerable in the face of the enormous Other; but the Other is also finally another part of ourself, the projection of our repressed infantile rage and desire (our blind drive to annihilate those toward whom we feel anger, to force satisfaction from those who stimulate us, to wrench food for ourselves if only by actually devouring those who feed us) that we have had in the name of civilization to repudiate (73).;

Clover assumes a viewer with a blank slate here (because she has to), but what if that viewer is a survivor of sexual abuse like me? In that scenario everything Clover writes gets turned up several notches. My fears and desires are not generalized but very specific; I get to project my “repressed infantile rage and desire,” my “blind drive to annihilate those toward whom [I] feel anger” into the horror film landscape. Horror films might be the only place where the truth of my abuse is allowed to exist uninflected by the feelings of others.

The other place my abuse is allowed to exist uninflected is with a really good therapist (which I have, thankfully). But even in therapy the agenda is clear: we’re going to get better here. We’re going to process what happened. In therapy there are no guarantees of safety. Indeed, the process if often quite fraught. In horror films, conversely, there is no therapeutic goal at all. Oddly enough, this is precisely why horror films feel safe to me. The rage, the hurt, the confusion, the fright–all of this can simply exist when I’m watching a horror film. I don’t have to make sense of any of it.

Going through trauma is like living in a horror film. Living with untreated trauma is like living in a horror film. Trauma is unspeakable, and horror films speak the unspeakable. Van der Kolk writes that Freud “believed that reenactments were an unconscious attempt to get control over a painful situation and that they eventually could lead to mastery and resolution” (32). Van der Kolk disagrees with this, and so do I. Van der Kolk believes that “for many traumatized people, reexposure to stress might provide a relief from anxiety” (33), but he also admits that when all is said and done, he can’t answer the basic question we started with: why do many traumatized people seek out experiences that would repel most of us?

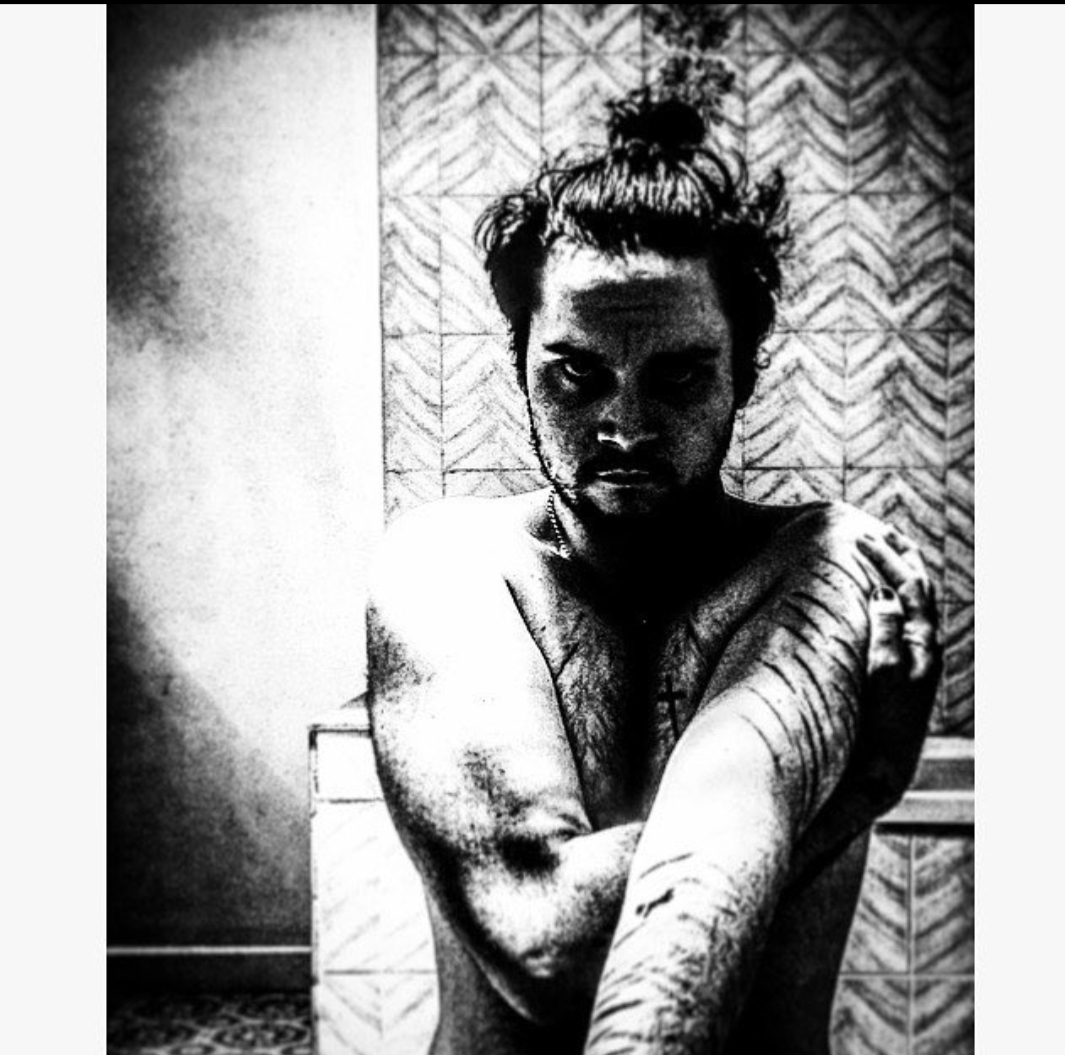

from Alexandre Aja’s 2003 High Tension

For me horror films provide a space of identification and comfort. They tell me I’m not alone. They understand what I went through, and they don’t judge me for struggling. The transgressive nature of them create a safe space for me to work out my own feelings about what happened to me and how I feel about it now.

Or maybe I’m full of shit. That’s a possibility too. All I know is that when I’m triggered out of my mind, nothing calms me down like the buzz of a chainsaw.

BONUS MATERIAL

Here’s a list of messed up movies to give you a sense of what’s out there (It’s worth noting some flaws to the list, most notably the absence of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and the inclusion of The Evil Dead remake, which was good but nowhere near as good as the original.)

WARNING: The following video contains upsetting images. You will likely be offended. Having said that, this is one of the best horror films ever made, and it shocks the viewer to see it. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre will open you up.

I am a big chicken, so I would never watch a horror movie ! My version of this was watching CSI! That’s about as gory as I get, it’s completely out of character compared to my other watching habits. As long as they caught the bad guy at the end it made me feel very satisfied. I never realized I was doing that, until I read this blog!