In the final section of “Song of Myself,” Whitman brings together the idea of death and the image of “grass” in the oft-cited “bootsoles” passage: “I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love, / If you want me again look for me under your bootsoles.” And a few lines later:

Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop somewhere waiting for you.

Here, the speaker of the poem documents his own death in a way that is both calming and reassuring. He gives himself over to death, a gesture made concrete by the act of giving himself to the earth. We, the readers of the poem, can find the speaker all around us in the earth, and if we fail, the speaker will wait to meet us wherever and whenever we die.

The contradiction here is that the speaker is both present and absent, something that hearkens back to the young Whitman who leaves home at 12. Though his family is physically absent from his life they will remain present in other ways—an extension of what child psychologists call object permanence.

I used the last two lines of “Song of Myself” as a dedication to my two sons in my novel, Speakers of the Dead. Like Whitman, my two boys moved away from their father when they were 14 and 12. When their mother and I divorced, she took them to live thousands of miles away, and though we keep in good touch, we simply cannot have the same relationship we did when we lived in the same house. We are both present and absent in each others’ lives.

My older son plays the bassoon in the Utah Youth Symphony, but I have only been to one of his performances. My younger son plays soccer, and is apparently quite good, but I have not been to any of the matches. I see my boys a few times a year, and our trips together have become week-long adventures with clear beginnings and ends. It’s thrilling to first see them, and we laugh like hell, and then as the end draws near our interactions become clunkier as we anticipate the separation. Saying goodbye is devastating.

A colleague, who is a poet, warned me that the most terrible part of losing your children in divorce is that they will never feel at home with you again. He was right. I think that’s what Whitman wants us to understand about death: that life continues without us. Or rather life continues with us, but not as we always wish. We are part of a grand series of comings and goings. Nothing collapses, but things sure do change.

~

~

Life has continued, for sure. Readers of this blog know what happened in between 2016 and 2020. The last line of the novel dedication is “I stop somewhere waiting for you.” I wrote it thinking that I would be waiting for my sons to come back to me in a way that would somehow reconstitute our relationship pre-divorce.

What I didn’t anticipate is that my sons were waiting for me too. And when I wasn’t able to reach out the way I wanted through my trauma recovery, they reached out to me. One insidious effect of trauma is the idea that relationships are one-way only. If I don’t feed the relationship, if I don’t give the other person something they want, then the other person will not want to be in the relationship with me.

I have felt that way as a father. Gareth and Eliot helped me understand the power of our relationship when I needed it the most, and I will always be grateful.

We haven’t seen each other since last summer, and since we’re in the middle of the pandemic, we don’t know when we’ll be able to see each other in the near future. Given all that, I feel my relationship with them is growing. I love talking to them on the phone, and I find myself in awe of them and their lives. They are thoughtful, intellectually curious, and terrific human beings.

And they’re my sons.

So Happy 21st Birthday, Gareth. And Happy 19th Birthday (in March), Eliot. I love you.

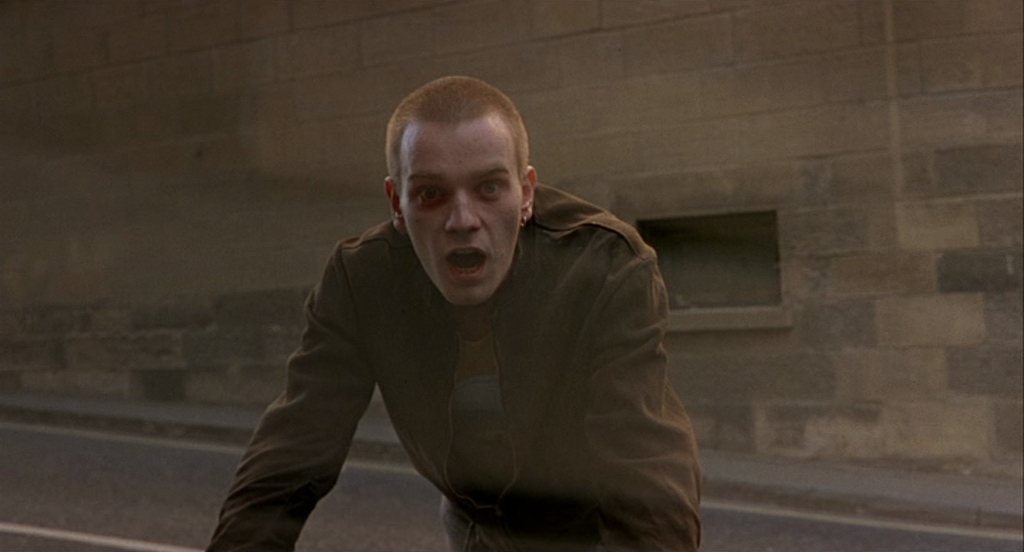

BONUS: Here’s Gareth, age 6, reciting Walt Whitman for the radio show, The Lumberyard:

Leave A Comment